The Fifth Kingdom - Chapter 11

FUNGAL ECOLOGY

Hotlinks to: the dung succession - amphibious

fungi in streams

aero-aquatic fungi in ponds - pine needle

succession

fire fungi - macrofungal ecology

- fairy rings - the humungous

fungus -

ATBI (All Taxa Biodiversity Inventory)

The Succession of

Coprophilous Fungi

The first habitat is dung (which is also known by many other names). We may turn up our noses, but to some other organisms, dung is a considerable resource, which is constantly being produced in large quantities by billions of animals all over the world. You may think that because it has passed through an animal's digestive tract, every bit of nutritional value will have been extracted from it. This is a false impression. There may not be a lot of high quality protein left, but there is a great deal of microbial biomass, as well as many food components, for example, cellulose, that neither the animal nor its gut flora managed to digest. There are also excretory products which, though they are of no further value to the animal, are high in nitrogen: herbivore dung may contain 4% nitrogen -- more, in fact, than the plant material originally eaten by the animal. So, at frequent intervals throughout its life, every mammal evacuates from its gut a mass of first class fungal substrate, simply asking to be exploited.

Are there fungi which specialize in exploiting dung? And if there are, how do they gain

access to this substrate when it becomes available? The answers may surprise you. About

175 genera of ascomycetes are largely or exclusively found on dung. The extremely advanced

and successful agaric genus Coprinus has many species that occur exclusively on

dung. There are also many specialized dung-inhabiting zygomycetes, among which Pilobolus

and some of the elaborate anamorphs in the order Kickxellales are perhaps the most

spectacular. So there is no doubt that a specialized mycota of dung-inhabiting (coprophilous)

fungi exists.

But how do they compete successfully for this substrate? The answer here may be a little

unexpected, but it is nevertheless perfectly logical. These fungi contrive to be first to

exploit the dung by the simple expedient of being in it when it is

deposited.

The only way to achieve that is to be eaten by the animal.

Coprophilous fungi manage this trick in several ingenious ways. These processes must

take into account some immutable logic. 1) The fungi are growing in the dung and will

therefore have to fruit on it. 2) Animals do not, in general, eat their own dung (though

rabbits do, raising interesting questions about the coprophilous fungi associated with

them). 3) Therefore, the spores must be somehow distanced from the dung in such a way as

to increase their likelihood of being eaten by herbivorous mammals.

You have already read in earlier chapters about how several fungi of herbivore dung

achieve this trick. How the zygomycete, Pilobolus, aims and shoots its sporangia

up to 2 metres toward the light.

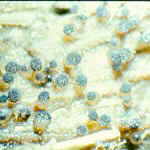

(photo above by W.R.West)

How the ascus tips of the apothecial ascomycete, Ascobolus, protrude from the

hymenium and bend toward the light before shooting their spores.

How the necks of the perithecial ascomata of Podospora and Sordaria bend

toward the light before their ascospores are expelled.

Each of these independently evolved phototropic

mechanisms is obviously designed to direct the spores away from any other adjacent dung,

and to increase the efficiency with which spores are deposited on nearby vegetation that

has a good chance of being eaten by the animal.

Many other dung-inhabiting fungi are less specialized than those I have just mentioned, or

have specializations so subtle that we have not yet detected them. Nevertheless, the fact

remains that with patient and repeated examination, we can find a large number of fungi

representing most of the major fungal groups on the dung of many herbivorous mammals.

Repeated

observations will show that the various fungi tend to sporulate in a reasonably definite

sequence. First the Zygomycetes

will appear...Pilobolus [above, right], and other

saprobic genera such as Mucor, Phycomyces, Thamnidium,

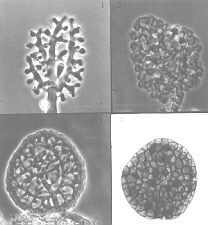

Helicostylum and others . Then the dichotomously branched sporangiophores of Piptocephalis

[bottom, right] which is parasitic on

some of the zygomycetes just mentioned...as

are Chaetocladium and Syncephalis [bottom, left].

The tall sporangiophores of Syncephalis [below] with their swollen apices and

linear merosporangia...

The graceful multiple recurved sporangia of Circinella minor (the three

pictures below show a developmental sequence...note the columellas in the

third picture.

Rhopalomyces elegans [below], which parasitizes nematode eggs...

Cunninghamella with its apical vesicle and unispored sporangia...

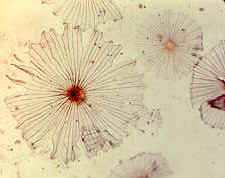

Then the Ascomycetes ..apothecial

fungi like Ascobolus...zooming in from left to right...

Saccobolus...again zooming in from left to right

Thecotheus...here with 32-spored asci

And the perithecial Podospora and Sordaria,

accompanied by a variety of conidial anamorphs (Hyphomycetes) such as the

blastic-sympodial Basifimbria...

...the nematode-trapping Arthrobotrys with its clustered didymosporous

(2-celled) conidia

and its various ways of snaring nematodes, including the 3-dimensional net shown here

[below, right]...

the synnematal, slimy-spored (arthropod-dispersed) Graphium, here shown in a

zoom sequence of four pictures...

the synnematal, dry-spored Cephalotrichum

(bottom, right)...

...and Trichurus, a synnematal hyphomycete with twisted, hair-like

setae arising all over the fertile head, which give

it a 'big hair' look (below)...

and finally the Basidiomycetes,

mainly small (but profuse) species of Coprinus...

It has been suggested that this is a true ecological succession, albeit a miniature

and condensed one. Initially it was postulated that the sequence was a nutritional one.

Zygomycetes can generally assimilate only fairly accessible carbon sources, such as

sugars. Their fast growth was assumed to give them an advantage in finding these, and

their early disappearance was thought to be due to the exhaustion of this substrate. The

ascomycetes and conidial anamorphs that appeared next were assumed to be able to

assimilate more complex carbon sources such as hemicellulose and cellulose; while the

basidiomycetes, appearing last and persisting longest, were able to exploit both cellulose

and lignin.

But when this hypothesis was scrutinized more carefully and tested by

experiment and further observation, it did not hold up. The growth rates of the various

fungi were found to be relatively similar, and the various carbon sources were not

exhausted as quickly as had been assumed. So a second hypothesis was advanced. This one

was based on the time it took for each kind of fungus to accumulate enough food reserves

to permit it to fruit. It was argued that the simple sporangiophores of the zygomycetes

could be developed after only a short period, while the more elaborate fruit bodies of the

ascomycetes would require a longer build-up, and the even larger basidiomata of the

coprini would need the longest preparation of all. This is a more reasonable hypothesis,

because if we grow some of the dung fungi on laboratory media, we find that it takes Mucor

hiemalis 2-3 days to sporulate, while Sordaria fimicola needs 9-10 days, and

Coprinus heptemerus 7-13 days.

Some of the Kickxellales, zygomycetes often found on the dung of sedentary mammals

(those with a defined home base, a small territory, and habitually used paths) produce

extremely complex and convoluted anamorphs.

Spirodactylon, possibly the most

complex of all, produces tall, branched sporangiophores that bear tiny coils within which

develop innumerable one-spored sporangia. The whole structure must be designed to catch on

the hairs of the rat or mouse as it passes by. This is made possible by the habits of the

animal which, although it doesn't eat its own dung, at least deposits it somewhere along

one of the trails it follows every day in its journeys to and from its den or burrow. The

final step, the ingestion of the spores, is presumably taken when the animal grooms

itself, as mammals (other than human children) habitually do. Some coprophilous

hyphomycetes (e.g. Graphium) produce slimy droplets of conidia at the top of tall

conidiophores or synnematal conidiomata. These spores are presumably dispersed by

arthropods which may themselves specialize in seeking out dung, and may thus act as

specific, and very efficient, vectors for the slimy-spored fungi.

Many other dung-inhabiting fungi are less specialized than those I have just

mentioned, or have specializations so subtle that we have not yet detected them.

Nevertheless, the fact remains that with patient and repeated examination, we can find a

large number of fungi representing most of the major fungal groups on the dung of many

herbivorous mammals. Repeated observations will show that the various fungi tend to

sporulate in a sequence. First, zygomycetes will appear; then ascomycetes and

conidial fungi, and finally basidiomycetes.

So we can assume that an assortment of spores of coprophilous fungi will be present in

dung when it is deposited, and that these will all have been triggered to germinate by

some aspect of passage through the mammalian gut. While Pilobolus is producing

its miniature artillery extravaganza, the other fungi are growing and assimilating

steadily within the dung, preparing for their own appearance at the surface. The new

hypothesis had neglected only one important factor: antagonism. After a few

weeks, almost the only fungi still sporulating on the dung will be species of Coprinus.

These can go on producing a sequence of ephemeral basidiomata for months. We now know that

the various components of the substrate are far from exhausted after the initial flushes

of growth and sporulation. What has really happened is that Coprinus has seized

control by suppressing most of the other fungi. Hyphae of Coprinus are actually

extremely antagonistic to those of many other coprophilous fungi. If a Coprinus

hypha touches one belonging to Ascobolus, the Ascobolus hypha collapses

within minutes. We don't understand exactly how this trick is done, but it is extremely

effective, and turns out to be a fairly common stratagem among the fungi, whose main

competitors for many substrates are other fungi

Another interesting and important gambit used by Coprinus involves repeated

anastomoses. Spores are more or less evenly dispersed throughout the dung when it is

deposited, and they all germinate more or less simultaneously, producing small mycelia

within the dung. When compatible mycelia meet, they will anastomose, and soon the entire

dung deposit is permeated by what is now essentially a single mycelium, which can then

pool its resources and produce more and larger basidiomata. Cooperation pays off for Coprinus.

There are also some interesting subplots that run concurrently with the main story.

Several of the zygomycetes that usually appear (e.g. Piptocephalis) are actually

parasitic on other zygomycetes. One common zygomycete, Rhopalomyces elegans,

parasitizes nematode eggs. Nematode-trapping fungi such as Arthrobotrys often

sporulate, and develop their characteristic rings and nets (see Chapter

15). Keratinolytic

hyphomycetes such as Microsporum (below) may appear on hair that the animal has

accidentally eaten during grooming.

Occasionally, an undescribed species of fungus may be seen. For many years the third

year mycology class at Waterloo followed the dung succession as a laboratory exercise.

These undergraduates saw the zygomycete Stylopage anomala on horse dung several

years before it was formally described in 1983. They also found an undescribed species of Podospora

(Ascomycetes), which is perhaps the 102nd species of this genus. They also found the rare

zygomycete, Helicocephalum, which I had never seen before.

Horse dung is easy to obtain in most areas, comes in discrete units, and can be handled

and observed without creating much personal distress. As many as 40 species of fungi

representing most major groups of eumycotan fungi are commonly recorded from a single

collection of horse dung. Most of them can be identified fairly easily with the help of

the specialized taxonomic literature that is now readily available, though I admit that

some of the zygomycetes are not easily recognized as such by beginners. Most of them could

be identified to genus with the help of the illustrations on this CD-ROM. Many of

the fungi can be isolated in pure culture without too much difficulty, and with a little

imagination, interesting experiments can be devised to investigate various aspects of

their behaviour. Perhaps now you can understand why I and many other teaching mycologists

ask our classes to put their culturally determined attitudes on hold, adopt an objective

scientific approach, and study the succession of fungi on horse dung, then think about the

biological mechanisms and manoeuvring that lie behind the visible manifestations. It's a

truly thought-provoking mycological experience.

Before we leave this topic I should warn you that you should not collect

and examine the dung of carnivores, because it might support fungi that

could also grow on you. However, in the interests of science, your

humble scribe checked out the dog do-do shown below, which had taken on

a transmogrified appearance in cool, humid weather. I found that the

principal fungus fruiting here is a species of Mucor (Zygomycetes).

I was probably quite safe, because the animal was eating kibble, not cats. But my advice is still the same: stick to herbivores...their droppings don't smell nearly so bad...

If you want to know more about the coprophilous fungi, I recommend

that you read a recent paper: Richardson, M.J. (2001) Diversity and

occurrence of coprophilous fungi. Mycol. Res. 105:

387-402.

I cannot close this section without mentioning a magnificent new book from an Italian physician, Dr. Francesco Doveri (see references). It has 1104 pages, 158 colour photographs and 300 other illustrations. It is undoubtedly the most extensive coverage yet afforded to coprophilous fungi, and took the author 15 years to bring this project to fruition. Definitely worth a look, if you can find a copy.

Now on to a very different habitat...

Amphibious Fungi in Streams

The second area of fungal ecology I want to examine is a stream flowing through a

woodland, somewhere in the temperate zone. We already know that the tiny chytrids and

oomycetes live here, but we might not expect to find many of the typically terrestrial

dikaryan fungi. However, if you collect some stream foam and examine it under the

microscope, you will see that the bubbles have trapped a rather unusual kind of

spore (this is simply a physical phenomenon -- a surface tension effect --

and there is no other relationship between the bubbles and the spores).

I collected foam in

winter from this stream near where I

live...

If you pass a litre of

this stream water through a filter, then stain the filter in cotton blue

and examine it through the microscope, you will see many large and strikingly

shaped fungal spores. Many, perhaps most, will be tetraradiate.

These two sets of drawings are from

a booklet published by Ingold (who discovered these strange fungi) in

1975.

You can see tha there is a wide

range of different morphologies, almost all of which share one feature -

they have arms or appendages sticking out in various directions.

We will see how these evolved...

Dark field picture of Lemonniera

conidia

Phase contrast photomicrograph of a

conidium of

Lemonniera aquatica

Clavariopsis aquatica

(phase contrast)

Tetracladium marchalianum

(interference contrast)

Articulospora tetracladia

(phase contrast)

Culicidospora gravida (phase contrast)

Others will be unbranched, long, thin

and arc-shaped, sinuate or sigmoid (s-shaped).

Anguillospora, a common sigmoid form

(phase contrast)

They are all produced by conidial

anamorphs that are specially adapted for living in streams.

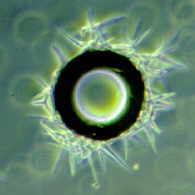

There are even yeasts with a tetraradiate arrangement of their

cells, presumably for the same reason this shape has been adopted by the

other spores. This photomicrograph is of Candida aquatica.

Where do these spores come from, and how do the fungi that produce them make a

living? The first clue came when limnologists (biologists specializing in freshwater

systems) began to examine the energy budgets of streams. Because some streams flow through

forests, they are heavily shaded during the growing season. This means that few green

plants (primary producers) can grow in them. It was found that more than half, and

sometimes nearly all, of the energy supporting organisms that live in streams comes from

autumn-shed leaves. This source of energy is described as 'allochthonous' (which means

'coming from somewhere else' just in case you wanted to know).

When they first fall into the water, these leaves are extremely unpalatable to stream

invertebrates, but as they are colonized and 'conditioned' by microorganisms, they

apparently become tastier. Experiments in which batches of leaves were treated with

either antifungal or antibacterial antibiotics showed that the fungi were chiefly

instrumental in making leaves palatable to animals such as Gammarus pseudolimnaeus,

a numerous amphipod crustacean living in the stream (another amphipod lives on

the beach below my house in

millions, eating decaying tidal jetsam, mostly seaweeds and, no doubt, the fungi growing on and in

them).

Gammarus, a detritivorous and mycophagous amphipod crustacean

In a feeding experiment, Gammarus (the dark,

comma-like objects) choose to eat fungal

mycelium (the greyish stuff at lower right) rather than unconditioned leaf

discs (dark circles).

Later experiments with leaves conditioned by individual stream fungi showed that not

only were some of the fungi that produce tetraradiate or sigmoid conidia most active in

conditioning leaves, but their mycelia and sporulating structures were also highly

nutritious food for detritivorous stream animals such as Gammarus

(Amphipoda, Crustacea). An important

ecological role had been established for these fungi.

But many questions remained. Were those fungi with tetraradiate spores related to one

another? Did they have teleomorphs? (which would help to answer the first question). Since

streams always flow the same way, and have a natural tendency to carry small things like

spores downstream, where did the inoculum for the upper reaches come from? What were the

advantages of the tetraradiate and sigmoid spore shapes? The information we needed was

gradually accumulated over several years of experiments, until eventually we were in a

position to give some answers.

Many of the tetraradiate (4-armed) spores, though similar in configuration

at maturity, developed in rather different ways. I will describe just two

of these. In some, three arms grew upward and outward from the top of the

first-formed arm. In others, one arm grew upward, the other three or four

outward and downward at the same time from a central cell. Some of these

conidia were thallic, some blastic. A few had clamp connections,

like Taeniospora gracilis, shown here, and were clearly basidiomycetous...

But most

didn't. This impression of diversity was confirmed when some of the teleomorphs were

discovered. Some were unitunicate ascomycetes, both operculate and inoperculate, producing

apothecial and perithecial ascomata. Some were bitunicate ascomycetes. Some were

basidiomycetes.

It became clear that the morphologically similar anamorphs were

actually a mixed bunch: fungi of very different origins that had undergone convergent

evolution, molded by selection pressure into similar shapes. The teleomorphs also provided

one answer to the question of how these fungi got upstream: ascomata and basidiomata,

unlike the anamorphs, were not submerged in streams, and they liberated airborne

ascospores or basidiospores. The group has been christened the amphibious fungi,

because of its immersed anamorphs and emergent teleomorphs.

But why did so many of these taxonomically diverse amphibious fungi evolve conidia with

similar shapes? It was found that as they were carried along by the water, tetraradiate

spores sometimes entered the layer of still water just above the surface of

submerged leaves, and then made three-point landings

on these leaves. We know that a tripod is the most stable configuration,

able to stand firm on irregular surfaces. The spores formed microscopic

tripods that gave them a foothold on the dead leaves for long enough to

germinate from the ends of the three arms, and attach themselves to the

substrate before being swept away.

Much of the

early work on stream fungi was done by Terence Ingold, who published many

papers on the strange fungi to be found on leaves in water, starting as

long ago as 1943.

The reason for the sigmoid shape has not yet been fully

established, but Webster and Davey (1984) published a paper: 'Sigmoid

conidial shape in aquatic fungi' in Transactions of the British

Mycological Society 83: 43-52. They observed that most such conidia

tended to roll along in flowing water with their long axes at right angles

to the current, though some vaulted end over end when they touched a

surface. Both kinds of movement bring the ends of the spore into

contact with the substrate. If the flow slows down (and it is almost

zero at the boundary layer next to the substrate), this gives the end of

the conidium a chance to stick to the surface. After attachment, the

conidia swing around and lie with their long axis parallel to the current,

and rarely become detached again. They then produce sticky appressoria,

and germinate quite quickly, apparently stimulated by the

contact.

Sigmoid conidia may represent an evolutionary compromise. Although not as efficient at attachment as tetraradiate spores, they represent a more efficient allocation of resources. As usual in the living world, there is more than one answer to a particular problem

After

colonizing the leaves, the amphibious fungi sporulate again, and it was found that they

would do this only in highly oxygenated conditions, and with the physical stimulus

provided by flowing water. It is clear that amphibious fungi

incorporate many special adaptations, both morphological and

physiological, to their environment.

If the spore numbers are charted over the entire year, it will be seen that their

numbers peak in Fall and Spring. In the first place, the massive new input of autumn-shed

leaves provides the necessary substrate. In the second case, spring run-off will also

carry plant debris into the stream. The entire process is diagrammatically summarized

below, showing that the fungi are vital intermediaries of energy flow in streams,

providing a link between dead leaves and trout.

Nikolcheva et al. (2005) have used molecular

techniques to explore diversity of fungi in the early stages of

colonization of leaves in streams (see references), and showed that after

initially high diversity, numbers of taxa fell as terrestrial fungi were

outcompeted by aquatic species, and aquatic species established their own

pecking order.

Aero-Aquatic Fungi in Ponds

One good aquatic habitat deserves another, so after sorting out the role of fungi in

streams, we switched our attention to woodland ponds (our third habitat).

The pond in question lay in the heart of the woods behind my house in

Waterloo.

Again, primary production within the pond was limited by the forest canopy. Again,

there was a specialized group of fungi living in the pond, though no-one knew if these

fungi played an important role in the ecology of the pond. In this case the fungal

propagules commonly found were hollow, and floated. Again, this end was achieved in

several different ways, of which I will describe only two. The pond has almost dried out

in summer (1) A conidiophore emerges from a dead leaf just below the surface of the the

water, and branches like a tree. Eventually, the ends of the fine branches all swell up

and fuse with their neighbours to form an air-filled, watertight structure. This is the

propagule of Beverwykella.

(2) Another conidiophore grows from a dead leaf, emerges through the water surface,

and its tip begins to grow in circles. Coiling repeatedly on itself in wider and wider,

then narrower and narrower gyres, it eventually builds a barrel-shaped, air-filled,

watertight structure. This is the propagule of Helicoon.

The fruit bodies (magnified X 10 in the top left picture, and X 50 in the top right picture)

are hollow, and are lined with non-shooting basidia (bottom right X

1500). Note the symmetrical mounting of the spores and the lack of a pointed

sterigma (see discussion in Chapter 5b).

A young basidium (bottom left) shows the typical clamp connection at its base.

Here is another apparently rare pond fungus, the tiny floating

gasteromycete, Limnoperdon. It has been recorded only from our pond in

Ontario and somewhere near Seattle, Washington, though it surely occurs at many places

between those widely separated localities -- people just haven't looked carefully.

Because these fungi live and grow under water, but produce their spores only above the

surface, they are called the aero-aquatic fungi. It's obvious that the

structures of the two kinds of conidia described above, though functionally

equivalent, are not closely related. Again, convergent evolution has been at work, the

selection pressure applied by some ecological imperative.

We finally discovered what this was. It was the need to be first on the scene when

new substrate appears. When a dead leaf falls into a pond, it does not sink immediately.

It may actually fall on top of some of the floating propagules just illustrated, or

the propagules may be drawn to the floating leaves by surface tension. In either case,

these fungi will be the first pond-adapted species to enter this new substrate. The leaves

soon sink to the bottom of the pond, carrying their new colonizers - hyphomycete or

gasteromycete - with them

These fungi also have the ability to grow at low oxygen levels, and to survive the

virtually anaerobic conditions that prevail at the bottom of a pond for extended periods

during the winter.

Sporulation will happen again when the pond begins to dry out during the following

summer, and the water level subsides until the colonized leaves are once more just below

the surface. We found that these aero-aquatic hyphomycetes play an ecological role

parallel to that of the amphibious fungi in streams: conditioning the dead leaves, and

making them palatable to the detritus-eating invertebrates such as snails, and vertebrates

such as frogs, whose larval stages live in the pond.

Frog spawn [below]

Produces tadpoles which skeletonize leaves

after the fungi have 'conditioned' them...

...and eventually metamorphose into

tree frogs [bottom] which represent the apex of the pyramid of life in the pond.

There are quite a few marine fungi, including

many ascomycetes, some hyphomycetes and a small number of basidiomycetes,

but all the evidence, both morphological and molecular, points to

terrestrial origins for these fungi.

Other Habitats

The biosphere has myriads of other habitats, each unique in various ways, and each making

special demands of the organisms that live in it. The roots of plants create special

conditions around themselves, and have established especially intimate relations with

hundreds of endotrophic and thousands of ectotrophic mycorrhizal fungi (which have Chapter 17 to themselves). Other rather less

specialized saprobic and parasitic fungi also abound on and near roots. The surface of

living leaves is inhabited by a specialized mycota, while dead and decaying leaves are

substrates for a succession of other species. The soil, into which most leaf remains are

incorporated, is itself a mass of microhabitats, and is the richest reservoir of fungal

diversity. And of course the leaves of different plants, and the various soil types, will

have different subsets of the total mycota. Juliet Frankland, in her

Presidential address to the British Mycological Society (reference below), gives a nice

overview of the problems and progress in our study of fungal succession, exemplifying them

with an autecological study of the agaric, Mycena galopus.

Not all fungi can be

parceled out neatly into successive steps of a succession. Often, fungi compete for

access to a substrate. Sometimes a natural phenomenon will give us an unexpected insight

into this struggle. Here is a picture of a block of wood which has been colonized by many

different mycelia. The boundaries between the 'territories' of different mycelia can be

clearly seen as black lines or zones, and the wood is described as 'spalted.'

The black material is melanin-like, oxidized and

polymerized phenolics deposited by wood-rotting fungi, and although the biological

function of the zones isn't entirely clear, melanins are the precursors of the humic

acids, which are long-lived and important determinants of soil fertility.

This kind of partition can even occur in much smaller substrates, such as individual

leaves, as in this one of Oregon grape (Mahonia) from John

Dean Provincial Park near where I live. The colonies and black fruit bodies shown are of Coccomyces

(Rhytismataceae, Ascomycetes). The lower pictures

are

close-ups, which show the unusual

polygonal outline and stellate opening

of the ascomata. Note that while the colonies in the

second picture have produced only one ascoma each, that in the third picture

has a larger territory, and has been able to develop multiple ascomata, now

open to expose the hymenium.

Another fungus exploiting leaves of

Mahonia is Cumminsiella (Pucciniaceae, Teliomycetes).

This fungus attacks living leaves, and thus preempts the saprobic

Coccomyces.

This time a single infection

occupies a whole leaf. The uredinial sori open on the lower surface of the

leaf.

There's more information on this fungus, including a photomicrograph of

urediniospores and a teliospore, in Chapter 5d.

This senescent salal (Gaultheria shallom) leaf has also

become divided up, but in this case two or three different fungi are involved.

Even if a leaf isn't subdivided into territories, after it dies you are

likely to see fungal colonies develop, as is happening in the Hosta

leaf (above, left) from our garden. The fungi in this case are mainly Cladosporium

and Epicoccum, two common saprobic hyphomycetes. The picture

on the right shows a part of another Hosta leaf, clearly

demonstrating that the areas covered by the fungal colonies, marked X, are

the first to be eaten by animals. We may compare the fungi to peanut

butter, and the leaf to the bread which it renders palatable.

Which brings me to the subject of my own PhD thesis -- the succession of fungi

involved in the long, slow decomposition of another kind of leaves -- Scots pine needles

(our fourth habitat).

I was presented with a problem which, briefly stated, was as follows. "When we isolate fungi from the soil, the majority of cultures will be of light-coloured fungi, while a majority of the hyphae seen in the soil are darkly pigmented. Figure out what's going on."

I chose to work in a pure stand of Scots pine (Pinus

sylvestris)

I looked at the various soil horizons

in the forest, and tried innumerable times to grow the dark hyphae, picking them out with a

micromanipulator and giving them a variety of delicious media. But they refised to

grow, so I eventually decided that most of them must be dead, and that they had perhaps

grown at some other time and in some other place. I looked in the organic horizon

above the mineral soil, and found there a thriving community of litter decomposing fungi,

which I proceeded to investigate (I did not realize it at the timer, but this is fairly

typical of PhD projects, which are often changed in mid-course by some unforeseen

event(s).

I embedded a small chunk of the Scots pine forest floor in cold-setting

resin, then cut it into vertical slices, one of which I drew for this illustration, which

shows the spatial distribution of needles, and their gradual transition from L >

F1 > F2 > H layers. I then decided to examine as many needles from each layer and

sub-layer as I could process each month (the number turned out to be 300 needles).

The vial (above) contains living needles from the tree, which

represented stage one in fungal colonization. Vial 2 = L layer (pale brown), vial 3

= upper F1(much darker, but still tough), vial 4 = lower F1 (blackish and softer), vial 5

= F2 (greyish and fragmenting). By the time litter material entered the H layer, it was no

longer recognizable as individual needles.

Needles were treated in various ways. (1) Some were washed repeatedly to remove loose

surface spores and plated out in segments to isolate fungi on and in the needles. (2) Some

were surface sterilized before plating out, to select for internal colonizers. (3)

Some were wax embedded and sectioned. (4) Some were observed directly over a period of

incubation in damp chambers.

This is a reference point -- a transverse section of a healthy,

living needle. Changes can be measured against this.

And here is one of the first dramatic changes, the development of numerous

ascomata of Lophodermium pinastri, which apparently often colonizes the interior

of living needles without producing overt symptoms. The death and fall of the needle

stimulates the fungus to fruit.

The large number of lenticular black ascomata of Lophodermium

that can occur in a single needle indicates a dominant colonizer. Here two ascomata are

seen in section.

Other fungi fruit in other needles -- note the several paths along which

individual needles may travel. In this picture, the fruit bodies are pycnidial

conidiomata of a coelomycetous anamorph, Fusicoccum (holomorph probably Botryosphaeria).

The interior of the needle can be seen to be breaking down under the attacks of the

fungus.

Meanwhile, on the surface of the needle, networks of dark hyphae (remember

them?) develop. But what fungi do they represent? Mycelium without sporulating

structures is not very helpful unless one has access to molecular techniques.

Fortunately, several of these fungi fruited either in nature or in the

damp chambers. The first of these is Slimacomyces monospora (which I

mistakenly described as a species of Helicoma in 1958!)

Here is a drawing of Slimacomyces monospora, with its single

helicosporous chlamydospores.

A second major surface colonizer is Sympodiella acicola which I

described as the type species of a new genus (It still stands). Again, note that the conidiophores are in an

almost pure stand.

Here is a drawing of Sympodiella acicola, showing that its unique

characteristics are that while its conidiophore extends sympodially, the conidia are

thallic-arthric (for those of you who are fans of

conidium development -- otherwise look back to Chapter 4).

Another fungus that is obviously at least partly internal develops

sclerotia and conidiophores. This was Thysanophora penicillioides...

And here is part of a Thysanophora conidiophore with a

penicillus (the brush-like conidiogenous apparatus - the numerous cells at

the top are phialides, which can each produce many conidia in a dry

chain).

Another pure stand of external conidiophores of an internal fungus, Verticicladium

trifidum (an anamorph connected to an apothecial fungus, Desmazierella acicola,

which I never saw). The conidiogenous cells of this fungus extend

sympodially during conidiogenesis.

Finally, we have arrived at the partitioning of needles among fungi.

It is particularly obvious here, where a darkly pigmented fungus squares off

against an apparently unpigmented fungus.

Section of a partitioned needle, showing the melanin barrier between

species. The fungus at upper left is Verticicladium; its neighbour is not

fruiting so cannot be identified. Compare this partition with the black lines shown

earlier in wood and leaf.

Now a new participant bursts onto the scene (well, it's aleady left, but

it has left its trademark - frass). Now the needles have been softened up by the

fungi, arthropods can eat the needle material. The frass identifies the intruder as

an oribatid mite.

And here it is, a miniature armoured tank that eats fungi and needle.

Now in the lower F1, the interior of the needle has collapsed or been

eaten, and the upper surface is coated with a deposit of frass, which contains many

fragments of fungal hyphae and spores.

This diagram plots the overall picture, following the needles through 9

years of mainly fungal decay. The width of each bar represents the relative

importance of the fungus at each stage. Darker bands show fruiting periods. At far left

the fungi are those that grow on or in living needles. As we move to the right, the fungi

involved in later stages of decay are traced.

Read this table carefully -- it will amaze you, and it shows just how

important fungi are in the forest ecosystem. Not merely important, but producing

greater biomass than any group other than the plants.

A recent paper by Paulus et al. (2003 - see references) gives

further insight into what is going on in decaying plant

litter. Using a particle filtration technique, these authors

isolated no fewer than 1365 isolates, representing 112-141 morphotaxa,

from 8 leaves of Neolitsea delabata in the tropical forests of

Queensland.

Fire fungi

Other special substrates have evoked their own suites of specialized fungi: keratin is attacked by some of the Onygenales (Ascomycetes) and their anamorphs; wood by many Aphyllophorales and some Agaricales. Extreme physical conditions (see fire, above) have selected specialist fungi which, by evolving the ability to cope with high or low temperatures, or low water activity, have essentially escaped from competition, and gained access to untapped food supplies. Some fungi are the most osmotolerant organisms known (see Chapter 20). The cycling of anamorph and teleomorph, which I mention many times in connection with plant disease fungi in Chapters 4 and 12, is often largely a matter of their response to specific ecological conditions, which turn on and off large segments of the genome. The fungal ecology of sewage, compost, mushroom beds, agricultural and forest soils, naturally decomposing plant remains, some cheeses, bread, wine and beer, crops in the field and after harvest, the air, the space between your toes, and the tissues of immune-deficient or immune-suppressed people: all can be the subjects of worthwhile, and even important, studies of fungal ecology. Many of the food webs illustrated in ecology textbooks miss out more than half of the organisms involved in the transfer of energy and nutrients. They often stress macroscopic organisms, while omitting microscopic organisms such as the saprobic and mycorrhizal fungi. This neglect is unfortunate, especially since we now appreciate that microorganisms, being at the base of food webs, provide nutrients and mutualistic symbionts for almost all plants and animals. The basic links in terrestrial food webs lie in the soil which is, of course, where a huge number of fungi still live. Every attempt to understand trophic systems must start and finish with soil organisms. And surely the fungi are among the most important of those.

Macrofungal

Ecology - Help wanted!

Most of the situations I have described in this chapter are small or

localized. If we consider the macroscopic fungi, and their roles in

such extensive ecosystems as forests, we find that the state of fungal

ecology is relatively primitive, meaning that we simply don't know very

much about how those fungi act and interact under natural

conditions. If you doubt this, you could explore the mycological

literature for information on where to find morels (in my opinion, the

best of all edible fungi). You will be led a merry dance, from old

apple orchards and dead elms to recently burned forests. Until

relatively recently, no-one even seemed to know whether morels were

mycorrhizal or not (my understanding is that they are opportunistic

saprobes, exploiting new substrates then fading away, only to appear

somewhere else when new food sources present themselves).

As for the ubiquitous agarics, which are undoubtedly the most widely collected and studied

of all fungi, I have to report that things aren't much better. Only Europe holds out a candle in the

darkness. Since europeans have been collecting and recording

macrofungi for centuries, they have the kind of database that allows the

present generation of mycologists to draw comparisons with the past.

This is why several European countries have 'Red Lists' compilations of

macrofungi which seem to have undergone serious declines in recent years

-- or even to have disappeared altogether. It is impossible to

produce such red lists for anywhere in North America because records do

not go back far enough and are, in any case, still fragmentary. Although we may suspect that certain species are

declining or disappearing, we have no well-documented historical reason

for saying so. You can find out more about red lists by googling 'red list

endangered fungi'.

We understand that about half of the known agarics are mycorrhizal -- they

have an intimate, mutually beneficial relationship with many of our forest

trees, and ecological research has recently begun to focus on the effects

on such fungi of various forest practices, and especially the

clear-cutting of old-growth forests which still (regrettably) goes on in

many jurisdictions, and most blatantly in British Columbia where I live.

One of my own graduate students has recently established that many of the

fungi associated with old growth forests do not re-colonize

clear-cut habitats for 40-50 years. And his suspicion is that

the recolonization happens by means of airborne basidiospores which

originate in nearby old growth. What if there is no longer any

nearby old growth to provide this inoculum? But International

logging companies carry on in blissful ignorance of any such

concerns.

Just when we think we have established a few

principles based on the occurrence of fruiting bodies of the mycorrhizal

fungi, it is demonstrated by molecular techniques that in many cases the fungi producing the

fungal sheaths around the roots of the trees are not those whose

basidiomata are appearing above ground. Are we back to square

one? No one seems sure at present. But I mention this to

demonstrate how little we actually know about macrofungal

ecology. Some recent studies (2005)

claim that the apparent disconnect is at least partly because many of the

mycorrhizal fungi develop small, inconspicuous, cryptic or seasonally

limited fruit bodies, rather

than the large and conspicuous ones detected by most collectors.

A fascinating study by Tofts and Orton (1998) points out that although they

have been collecting agarics regularly in a particular woodland in

Scotland for 21 years, and have recorded 502 species in that time, each

year they still find species they have never seen before. Over twenty

years of collecting, and they still cannot say that they have a proper handle on agaric biodiversity in that woodland. They suggest that

at

least 25 to 30 years of collecting, and possibly more, will be necessary

before that goal can be attained.

An even more recent paper by Straatsma, Ayer and Egli (2001) emphasizes

many of the same points. They collected basidiomata weekly for 21

years (1975-1999, except for 1980-1983), and recorded over 400 species in

a 1500 m2 plot. Yet only 8 species were found every

year. The number of species/year ranged from 18 to 194, and even in

the last year of the study, 19 species appeared which had not previously

been found. Clearly, the authors had not seen the full diversity of

macrofungi.

A group of west-coast mycologists (including Paul Kroeger, Christine

Roberts, Oluna and Adolf Ceska, and me), supported by the Mellon

Foundation, has been doing a macrofungal inventory of Clayoquot Sound on

the west coast of Vancouver Island. Over 5 years, visiting once in

spring and twice in fall, we have collected 660 species. Two of the

most interesting features of our study have been: (1) that

only 38 species were found every year and 407 were found only once, and

(2) that a large number of fungi new to the study cropped up

each year. After year one, we have found about 100 additional

species each year.

In Fall 2004 the Cascade Mycological Society held its 16th successive mushroom fair at the Mount Pisgah Arboretum just outside Eugene, Oregon. As a guest speaker for the Society I was fortunate enough to be invited to participate in the collecting trips leading up to the fair. The fair is an exciting introduction to the larger fungi because over 300 species are usually on display - speaking to a huge effort on the part of the members. I was also fortunate enough to get my hands on the statistics for all sixteen years. Over those years just over 700 species have been recorded from the area. When we arranged the data according to the number of years in which each species had been collected, an interesting picture emerged.

To begin with the extremes. I was rather surprised to discover that only 37 species (just over 5% of the total number) had been found in all sixteen years. It was equally thought-provoking to learn that no fewer than 190 species (almost a third of the total) had been recorded only once in those 16 years. Here is the list of species versus years.

Species No.

of years recorded

37

16

44

15

31

14

24

13

20

12

13

11

18

10

18

9

22

8

22

7

22

6

41

5

29

4

48

3

92

2

190

1

There are possible flaws in the data set. For example, species may have been misidentified. But the general trend is obvious. A relatively small number of taxa will show up every year, or almost every year, while a much larger number of taxa will be found much less often, and a very large number will be encountered only once every decade or so.

How many more taxa will show up in the years to come? What is the full number of species that the Cascade group can expect to find if they keep at it long enough? If we may be allowed to take a quick look in the crystal ball, might we not find that after 50 years they will have found 1,000 species?

This data set (for which I am indebted to the hardworking collectors and record-keepers of the Cascade Mycological Society) points up the necessity for very long-term studies wherever the diversity of fungi is to be fully explored, and calls for the accumulation of much concurrent data on weather conditions and other ecological factors if we are to understand why some fungi are so notably shy.

These reports are not intended to put you off, to deter you from getting involved in fungal ecology. Rather the reverse. It is clear that the need for research in this area is critical. We need good ecological studies just as much as we need molecular research on fungi. Some groundwork has been done in Britain, where the macrofungal assemblages characteristic of many habitats have been broadly outlined. But this is still far from an understanding of the full role played by those fungi in the habitats being considered. The need for seminal research has never been greater. The next section discusses some of that.Fairy Rings

Fairy rings are one of the few fungal phenomena that most people have seen. To the superstitious mind the arrangement of the fruit bodies in a circle might seem very strange. On top of that, the grass often doesn’t grow just inside the fruiting zone, so it looks really weird, and it isn’t too surprising that in the past, people ascribed such rings to supernatural events (fairies or witches dancing).

The real explanation is simple enough, once you know that mushrooms start life as microscopic spores that germinate, develop branching hyphae, and soon grow outward from their point of origin as a mycelium that tends to spread equally in all directions (see Chapter 3a), and thus forms a colony that describes an ever-widening circle in the soil. When the mycelium has accumulated enough food, and conditions are right, mushrooms develop at the periphery of the circle, finally bringing the previously invisible colony to our attention.

Fairy rings become larger every year, as the mycelium grows outward, always looking for food. It can’t turn back because it has used up the food resources behind it. Growth of the grass is inhibited because the dense fungal mycelium prevents water from penetrating the soil, and possibly because the fungus has released metabolites inimical to the plants. The grass inside the rings sometimes grows more lush, because the fungus has liberated nitrogen by its activities. Some rings, on places such as Salisbury Plain in England, that have been under grass for many centuries, are estimated to be at least 400 years old. It is quite possible that much larger and therefore even older ones could be found. You might keep your eyes open.

Many species of agarics (perhaps as many as 60) produce fairy rings. The most obvious are those which occur in pasture, and are often generated by species of Agaricus (see Chapter 5b), or by Marasmius oreades, which is actually called the 'fairy ring mushroom' (see photograph below). Sometimes another kind of fairy ring develops around trees, as mycorrhizal fungi grow outward from the roots.

The Humungous Fungus

Some years ago, mycologists were working on a forest in Michigan where three

species of Armillaria, well known pathogens, had been causing

trouble. They found that one of these species, Armillaria gallica,

seemed to be monopolizing a large area of the forest - 15 hectares.

When molecular biologists checked samples from within this area, they

found that all belonged to a single genet (a product of sexual

reproduction). So here was a single species of mushroom that had

spread through the soil and covered an amazing 15 hectares (35

acres). How was this achieved?

Armillaria

gallica apparently had a secret weapon. It soon became apparent

that this was its rhizomorphs, well-organized hyphal strands with

conducting hyphae in the centre, and a dark protective rind on the

outside, which help this fungus spread through the soil protected from the

hostile influences so common in this medium. Armillaria gallica

sends out rhizomorphs through the soil in search of new food

substrates. It isn't a particularly pathogenic species, so its

rhizomorphs wait patiently until a tree is weakened or dead before

invading. Having established its new base, it sends out more

rhizomorphs...

Sampling

established that there were about 10 tonnes of rhizomorphs in the

genet. If the fine assimilative hyphae and other structures were

factored in, the total mass of the colony/genet added up to 100 tonnes -

about the size of a blue whale. It was also calculated that the

colony was at least 1500 years old.

No sooner had the credentials of this fungus been established than a larger genet was discovered in Washington State. This one belonged

to Armillaria ostoyae, the common west coast species of Armillaria, and it

covered an almost incredible 600 hectares (1500 acres). Even more

recently, an even larger genet of Armillaria ostoyae has been

identified in the Blue Mountains of north-eastern Oregon: this one covers

2200 acres (about 900 hectares) and is estimated to be

between 2,400 and 8,500 years

old. This is

among the largest and most extensive organisms on earth. Who said

fungi were insignificant?

Diploidization-Haploidization and

Genetic

mosaics in Armillaria

It is possible that one of the reasons for the long-lasting success of

these species is a rather radical departure from the genetic norm.

It has recently been discovered that in Armillaria gallica and

A. tabescens, the

individual nuclei in the cells of the mycelia and of the non-basidial

parts of the species are haploid (not dikaryotic). This shows that

before the mushroom developed, there must have been events similar to

those that usually occur only in the basidia - the fusion of two

compatible nuclei and a subsequent reduction division: an extra-basidial

diploidization-haploidization event. It is obvious that for each

such event, new genetic variation is introduced to the organism

(crossing-over during meiosis ensures this) So mushrooms of at least

two Armillaria species are apparently mosaics of genetically distinct

nuclei. When these nuclei are incorporated into basidia, and undergo yet

another diploidization-haploidization event, even more diversity is

introduced to the organism. Since species of Armillaria

represent some of the largest and oldest organisms on Earth, it seems

possible that this 'mosaicism' may confer additional genetic flexibility

on these organisms, thus contributing to their amazing success. This

development of genetic mosaics has thus far been discovered in only two

species of Armillaria, but it is apparent that we are at the

beginning of another area of genetic exploration and discovery in the

mushrooms (see Peabody et al. refs below).

An article by Tom Volk, which can also be found here

is reproduced below. It is

written in an accessible style, and has some good pictures -- I'm pretty

sure you will enjoy reading it!

The Humongous Fungus--Ten Years Later

Thomas J. Volk, Department of

Biology, University of Wisconsin- La Crosse, La Crosse, WI 54601

volk.thom@uwlax.edu

Has it already been ten years? On April 2, 1992, the non-mycological world

first became aware of very large fungi, thanks to the efforts of Myron

Smith, Johann Bruhn, and Jim Anderson. They published a landmark

article in Nature (Smith , M., J. Bruhn and J. Anderson, 1992. The

fungus Armillaria bulbosa is among the largest and oldest living

organisms. Nature 356:428-431), but no one expected the media blitz

and the scientific interest that would follow.

First you'll need to know a bit of background on Armillaria, also known as the Honey Mushroom. Armillaria (Fr.:Fr.) Staude is a genus of mostly pathogenic agaric fungi. Perhaps the most important aspect of the life cycle of Armillaria is the formation of rhizomorphs, conglomerations of differentiated parallel hyphae with a protective melanized black rind on the outside. The rhizomorphs are able to transport food and other materials long distances, thus allowing the fungus to grow through nutrient poor areas located between large food sources such as stumps. The rhizomorphs can also act as "scouts" for the rest of the thallus, searching for new food sources. These proliferative rhizomorphs apparently permit Armillaria colonies to spread and become quite large. Thus enters the Humongous Fungus.

The science that led to this seminal Nature publication (Smith et al. 1992) turns out to be quite interesting and very thorough. The project was actually an offshoot of a grant from the Department of Defense, which funded a project to study the possible biological effects of ELF (Extra Low Frequency) stations in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. These ELF stations were built to communicate underground with ocean-going submarines in time of war. The humongous fungus site, which Johann Bruhn had been studying for many years, was actually one of the control sites, nowhere near the ELF stations. Historically, the site (near Crystal Falls, Michigan near the Wisconsin border) had been mostly northern red oak/white birch/ sugar maple forest, but the native trees had been harvested with more profitable red pines planted in their place. When the oaks were cut, the stumps were mostly left in the ground to rot. The oaks had been infected with Armillaria root rot, but had survived very well because they were not under any stress. However, when pines were planted, some species of Armillaria were able to kill the young pine seedlings. The particular species that garnered their attention was Armillaria bulbosa, which is now correctly known as Armillaria gallica. I'll tell you more about this taxonomic problem later.

The study of Smith et al. (1992) was performed by collecting vegetative mycelium of Armillaria by "baiting" with small pieces of poplar wood, actually popsicle stick-like tongue depressors. Since Armillaria is a wood decay fungus, the mycelium quickly colonized the tongue depressors. The labeled inoculum stick could then be easily collected. Additional subcultures, including tissues and single spore isolates, were made directly from fruiting bodies that appeared in the fall or from the black rhizomorphs and mycelial fans that are always present in the soil or on the wood, especially under the bark. The laborious process of analysis began, first with checking the mating type loci by mating on media in Petri dishes. Molecular techniques were then employed, first looking at mitochondrial DNA (mDNA) restriction patterns. These were both good markers for the study because mating type loci and mDNA restriction patterns are both highly variable within Armillaria species. Once these were determined, RAPD (Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA) and RFLP (Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphisms) markers were employed to check for additional heterozygous loci in the nuclear genome. With these several types of data, they could begin to draw maps of the area to determine the limits of each individual. One of these clones turned out to be quite large, covering 15 hectares (37 acres). Within this area, all the vegetative isolates had the same mating type , the same mDNA restriction pattern, and had the same eleven RAPD products and five RFLP-based markers, each marking a heterozygous locus. These data indicated that this 15 hectare clone is a single organism. However, some argued that this only meant that they had the same alleles at these genetic loci, bringing up the possibility that the samples were from separate, but closely related organisms (or individuals) that arose from separate matings. In their paper, Smith et al. (1992) presented some complex statistics that show that the probability of this being the case was infinitesimally small (P= 0.0013), given that all the samples share all the heterozygous markers examined. Even so, to lend even more credence to their conclusions, eventually they tested 20 RAPD and 27 nuclear restriction fragments that were found to be invariable in the large clone. By far the most likely hypothesis is that this clone reached it enormous size through vegetative growth. Thus the Armillaria clone was proven to be quite a humongous fungus. By estimating (very conservatively, I might add) the growth rate of the fungus under their natural conditions and by extrapolating the weight of the clone from smaller soil samples (again very conservatively), Smith et al. found the clone to be at least 1500 years old and weigh at least 9,700 kg (more than 21,000 pounds or 100 tons), close to the mass of an adult blue whale. They compared the mass to that of a giant redwood (Sequoiadendron giganteum) estimated to be about 1,000 tons, most of which is dead xylem tissue. The conclusion of their paper states, "This is the first report estimating the minimum size, mass, and age of an unambiguously defined fungal individual. Although the number of observations for plants and animals is much greater, members of the fungal kingdom should now be recognized as among the oldest and largest organisms on earth."

Myron Smith wrote to me recently in an email "I have often been asked something like,'what made you look for a large fungus?' Like most discoveries (and this is a point that needs to be stressed to granting agencies), we did not set out to make this discovery. Initially, (at least when Jim and I came on the scene) we wanted to find out how mitochondrial DNA was inherited in fungi in nature (Smith, Duchesne, Bruhn and Anderson, 1990). The first year we went out and sampled from a 120 x 60 m area. Nearly every sample was identical for mDNA and mating type. The second year we extended our sampling over a 1 km transect through the area and, again, detected this one wide-spread genotype. By extending the areas sampled in subsequent years, we were finally able to delimit the large area occupied by this genotype and then go on to show that this genotype likely represents an 'individual'."

Although they knew they were publishing a very good paper, Smith, Bruhn, and Anderson never expected what happened next. On that historic publication day, the furor began. Johann Bruhn, at that time at Michigan Technological University in Houghton, Michigan, now at the University of Missouri- Columbia, received the first of many phone calls from the media. Since it was April 2, he thought that this was a late April Fool's joke, but soon more calls began pouring in. All of the major television networks called; all of the major newspapers called from around the world. CNN called and reported that they had a plane in the air and would Johann please drive over to the site and wave so that they could take photos of the fungus. One Japanese businessman called and wanted to set up a partnership to build a boardwalk around the humongous fungus and charge people to view "the pulsating mass of fungus" that was there. Johann reports shutting himself into his office and having the secretary screen the calls one at a time as they came in. The two authors at the University of Toronto, Myron Smith (now at Carleton University in Ottawa) and Jim Anderson (still at the University of Toronto) experienced a similar media deluge. I first became aware of the media hype as I heard Jim Anderson being interviewed on US National Public Radio. You'll have to talk to the three authors to hear further interesting stories.

The media blitz lasted a month or so, then seemed to dissipate as things got back to normal. However, on May 18, 1992, it all began again. Terry Shaw, then in Colorado with the US Forest Service, and Ken Russell, of the Washington DNR, reported that they had been working on an even larger fungus, Armillaria ostoyae, that covered over 600 hectares (1500 acres, 2.5 square miles) south of Mt. Adams in southwestern Washington. The newspaper headlines read "Humongous Fungus has BIG brother out west." The fungus wars had begun. Who had the larger fungus? Questions arose as to who had better proof that theirs was a single organism. Russell and Shaw had only shown that the mating type loci were the same, but they had beautiful aerial photos showing growth of the large colony in a radial pattern, showing where it had killed the conifer trees. Smith et al. had a much more convincing argument, with several meticulous lines of genetic evidence showing without a doubt that theirs was a single clone.

Ten years later, we are still experiencing the fungus wars. In August of 2000, Catherine Parks of the US Forest Service in Oregon (along with collaborators Brennan Ferguson, Oregon State University; Tina Dreisbach, PNW Research Station, Forest Service; Greg Filip, Oregon State University; and Craig Schmitt, Wallowa-Whitman National Forest, Forest Service) reported that they had found an even larger fungus (again Armillaria ostoyae) in the Blue Mountains/ Malheur National Forest in Eastern Oregon. Their fungus is nearly 900 hectares (2,200 acres or 3.4 square miles or "as large as 1,665 football fields") and is estimated to be more than 2,400 years old. They used methods similar to those of Smith et al., including mating type analysis, but with the addition of DNA fingerprinting, not widely available in 1992. It seems likely that there are larger Armillaria clones out there somewhere. Myron Smith wrote to me: "As far as I (and I think this is true for Johann and Jim as well) was concerned, the 'Fungus wars' were a non issue; another example of sensationalistic journalism. The chance of finding "the largest fungus" is incredibly small. Our main point was how to unambiguously identify a genetic individual. That we did find a large individual by chance, however, suggested to us that massive, old fungi are probably not uncommon."

One interesting offshoot of these findings of humongous fungi has been a scientific discussion of "what exactly is an organism?" Most people understand the concept of an organism in an animal, which has very carefully defined limits--and most of it is usually visible as it moves around. However, much of a typical plant and most of a typical fungus is not visible to the naked eye. In particular with fungi, the limits of the individual are not clearly defined. The large question was "are these humongous fungi acting as single organisms?" It was well proven that the genetics of various parts of the humongous fungus organism are identical, but can, for example, one part of the organism communicate with other parts of the organism? Do they share physiology? If different parts are growing through different substrates, are they supplying other parts of the fungus with missing nutrients? Several articles began to appear in the scientific literature including Gould (1992) in which he spent a great deal of time discussing populations of asexually reproducing aphids. One letter to the editor by James Bullock of Oxford University (1992) pointed out some larger clones of plants, including an aspen clone (Populus tremuloides) covering 81 hectares and over 10,000 years old. At that time Bullock did not know about the larger A. ostoyae clones.

Despite the large size of the mycelia of these humongous fungi, the fruiting bodies (mushrooms) are really quite average in size. However, during a good fruiting season, the honey mushrooms may be quite abundant, producing a widespread biomass. However, the largest single fruiting bodies are produced by perennial polypores (shelf fungi), such as Bridgeoporus nobilissimus, Rigidoporus ulmarius, and even Ganoderma applanatum. Some of these large fruiting bodies may weigh over 160 kg or 300 pounds! Certainly these are much larger than Armillaria fruiting bodies, which are typically 50-100 g each.

I promised to tell you something about why Armillaria gallica is the name we should use for this species rather than A. bulbosa. Armillaria species typically produce a white spore print and have attached to decurrent gills. Most species have an annulus. Delimiting species in fungi is often difficult, but in Armillaria the biological species concept, based on mating compatibility, has gained wide acceptance. Until the late 1970's Armillaria mellea (Vahl:Fr.) Kummer was considered by most researchers to be a pleiomorphic (highly variable) species with a wide host range and distribution. The pathology literature on A. mellea was extremely confusing. The fungus was considered by different researchers to be either a virulent pathogen, an opportunistic pathogen, or an innocuous saprobe. Its host range was one of the broadest known for fungi. It was clear that more than one species must be involved. Because of the difficulty with studying the basidiomata using traditional characters, other methods of study were devised. Hintikka (1973) developed a technique that allowed determination of mating (incompatibility) types in Armillaria based on culture morphology of single-spored (haploid) pairings. He and his colleagues found six biological species in Europe. The work was extended into North America, where Anderson and Ullrich (1979) demonstrated that what had been considered as Armillaria mellea in North America was actually 10 genetically isolated biological species (North American Biological Species or NABS). Anderson, Korhonen, and Ullrich (1983) found that most of the biological species of Europe (including A. gallica, NABS VII or EBS E) were also represented in North America, although the reverse was not true.

There is a bit of controversy about what to call this species. Very briefly, the name A. bulbosa Velenovský (1927) [a.k.a. A. bulbosa (Barla) Velenovský, but Barla's (1887) name A. mellea var. bulbosa was illegitimate] has a very poorly preserved type specimen. Vladimir Antonín (1986, 1990) of the Czech Republic has examined Velenovský's type specimens (preserved in a liquid fixative) and has concluded that the specimen could be any of three species. According to Marxmüller (1992) Velenovský's species is identical with A. cepistipes Velen. (1920), which has priority, being an older name (see also Termorshuizen and Arnolds, 1987). Another name proposed for this species has been Armillaria lutea Gillet, but this species lacks a type specimen, and Gillet's (1874) description could represent any one of three species. Armillaria gallica Marxmüller & Romagnesi (1987), which has an excellent type specimens and abundant cultures, is the only name that can unequivocally be assigned to European Biological Species E and NABS VII. See Volk & Burdsall (1995) for a clear explanation of this taxonomic problem.

No matter what we call the species, the people of Crystal Falls, Michigan have become quite enamored with the nearby humongous fungus. They now hold an annual "Fungus Fest" every September. You can buy a humongous fungus burger (unfortunately not made with Armillaria, which is in fact a delicious edible mushroom) or fungus fudge (for some reason this does not sound appealing to me...) in their restaurants. Humungus (sic) Fungus t-shirts are available in their stores, but few people from Crystal Falls have ever seen the humongous fungus or could identify its fruiting bodies. In fact, the picture on their humongous fungus web page (http://www.crystalfalls.org/humongou.htm - DEAD LINK) is clearly a Leccinum, a bolete. Yes, I have told them about it, and yes, I offered them the use of one of my pictures of Armillaria. I tried.

The humongous fungus has been great publicity for the science of Mycology; we couldn't buy publicity like this. The humongous fungus even made David Letterman's Top 10 list. (see www.crystalfalls.org).

U-Haul, known for their truck rental services, got into the act in about 1997, when they contacted me for more information about the humongous fungus. Famous for publicizing some of the more bizarre "roadside attractions" on their trucks, U-Haul planned on putting the humongous fungus on some of their trucks to honor the state of Michigan. Through my web page, they contacted me and asked to use one of my pictures. I consented, hoping to help promote mycology to the masses. A month later they sent me a sample drawing for my approval-and the mushrooms were PINK! I diplomatically pointed out that in fact the mushrooms were not pink and that they should put them on the truck in their natural tan/brown/yellow color, since there were thousands of professional and amateur mycologists throughout North America who would know that their fungi were discolored. The U-Haul people replied back that they had taken some "artistic license" with the color, since they thought the natural color was not exciting enough. Sheesh. So now there are several hundred U-Haul trucks around the continent with pink Armillaria fruiting bodies on them. U-Haul now even has a website about the humongous fungus (Anonymous 2002A). It's exciting for me to see one of my pictures (well, sort of one of my pictures...) on one of the 500 or so Humongous Fungus trucks as I drive down the highway-- I've seen the humongous fungus trucks from Maine to California, from Minneapolis to Houston. I like to think it's helping to make the public more aware of fungi and mycology. Myron Smith again wrote: "I like to think that what grabbed the imagination of the public in this case was the idea that there are common, unseen things all around us that are magnificent. Of course, the mental image of a large, old fungus lumbering over the countryside is also bizarre and wonderful."

The humongous fungus continues to be a great boon for educating non-mycologists on the importance of fungi in their lives. The important publicity generated by the work of Myron Smith, Johann Bruhn, Jim Anderson, and the others that followed continues to speak well for the science of Mycology. Even more humongous fungi will no doubt continue to be found. As mycologists we have a multitude of Armillaria researchers to thank for putting mycology in the news in favorable light for a very long period of time. Mycology is not likely to get such great publicity again in our lifetimes. But you never know...

Acknowledgments: Thanks to Myron Smith, Jim Anderson, Dan Czederpiltz, and Sean Westmoreland for reading the manuscript and making helpful suggestions.

References

- Anderson JB, Ullrich RC (1979) Biological species of Armillaria in North America. Mycologia 71: 402?414

- Anderson JB, Korhonen K, Ullrich RC (1980) Relationships between European and North American biological species of Armillaria mellea. Exper. Mycol. 4: 87?95.

- Anonymous. 2002A.U-Haul Humongous fungus web page http://www.uhaul.com/supergraphics/fungus/ - DEAD LINK

- Anonymous. 2002B. Crystal Falls Fungus Fest

webpages. DEAD LINK

DEAD LINK - Antonín V (1986) Studies in annulate species of Armillaria - I Study of type-specimens of Armillaria cepaestipes Velenovský. Ceská Mykol. (Praha) 40: 38-40.

- Antonín V (1990) Studies in annulate species of Armillaria - III. Species described by Josef Velenovský. Acta Mus. Moraviae Sci. Nat. 75: 129-132.

- Barla G (1887) Bull. Soc. Mycol. France 3:143

- Dodge SR (2001) An Even More Humongous Fungus, LINK

- Bollock J (1992) Huge organisms. New Scientist 30 May, p. 54

- Gillet C-C (1874) Les Hymenomycètes ou description de tous les champignons (Fungi) qui croissent en France.

- Gould SJ (1992) A humongous Fungus Among Us. Natural History, July p. 10-14.

- Herink J (1973) Taxonomie Václavky Obecné? Armillaria mellea (Vahl. ex Fr.) Kumm. pp. 21?48. In: Vysoká Skola Zem_d_lska V Brné. Vyznamenaná Rádem Prace BRNO; J. Hasek, ed. Brno: Lesnicka fakulta VSZ.

- Hintikka V (1973) A note on the polarity of Armillariella mellea. Karstenia 13:32?39.

- Marxmüller H (1992) Some notes on the Taxonomy and Nomenclature of five European Armillaria species. Mycotaxon 44 (2): 267-274.

- Marxmüller H, Romagnesi H (1987) Bull. Soc. Mycol. France 103:152

- Shaw CT, Kile GA (1991) Armillaria root disease. Agriculture handbook 691, 233 pp.

- Smith M, Bruhn J, Anderson J (1992) The fungus Armillaria bulbosa is among the largest and oldest living organisms. Nature 356:428-431

- Smith ML, Duchesne LC, Bruhn JN, Anderson JB (1990) Mitochondrial genetics in a natural population of the plant pathogen Armillaria. Genetics 126: 575-582

- Termorshuizen A, Arnolds E (1987) On the nomenclature of the European species of the Armillaria mellea group. Mycotaxon 30: 101-116.

- Velenovský J (1920) Ceské Houby 1: 1-950

- Velenovský J (1927) Václavka hlíznatá (Armillaria bulbosa Barla) Mykologia (Praha) 4: 116-117; translation to English by Vladimír Antonín. (Pers. Comm.)

- Volk TJ, Burdsall HH Jr. (1995) Nomenclatural study of Armillaria and Armillariella species (Basidiomycotina, Tricholomataceae) Fungiflora, Oslo, Norway: Synopsis Fungorum 8, 121 pp. ISBN 82-90724-14-4

- Volk TJ (1995-2002) Tom Volk's fungi. TomVolkFungi.net